Climate Change

Tuolumne River, CA

Project: Don Pedro Reservoir

Understand how climate change impacts hydrologic processes

The worldwide trend in air temperatures in Figure 1 is a catalyst for studies on the effects of climate change for water resources (reported by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [Climate Change 2007, AR4 www.ipcc.ch]).

Hydrologists and meteorologists have assumed that the climate was stable – that observations like streamflows or average monthly temperatures in a watershed would (for “practical purposes,” like reservoir design) be drawn from the same statistical distribution. Most instrumental records are less than 100 year in length – the first stream gage in the United States was installed in 1889 on the Rio Grande in New Mexico . Without millennia long instrumental records, it is not possible to conclude that the temperatures in Figure 1 show “climate change” rather than long term cyclical behavior.

The earth’s climate has been very different in geologic time and has been significantly different even within the current interglacial warm period (the last 10,000 years). Volcanic eruptions affect worldwide temperatures. The assumption that the climate is stable is an argument about the rate of change of climate: that even though climate change is certainly occurring, the rate of climate change is so slow that the stable climate assumption is justified.

Within the last ten years additional lines of inquiry have made the stable climate/slow climate change hypothesis doubtful.

Schedule Your HFAM Demo.

Evidence, and possibilities, for more rapid climate change:

Observations of glacial melt in Greenland

Reduced polar ice and permafrost melt

Correlations between past warm periods and atmospheric gases (especially CO2)

GCM projections of the effects of greenhouse gases on future atmospheric temperatures

Water resource systems (reservoirs, aqueducts, irrigation systems) take decades to plan and build. If climate change affects existing facilities or makes new facilities necessary it is imprudent to ignore possible climate change effects.

The extent of “warming” is not clear – models differ among themselves and projections depend on assumptions about future greenhouse gas concentrations. Projections vary geographically – it’s clear that polar regions experience the largest temperature increases. Effects for other meteorological time series: precipitation, potential evapotranspiration, solar radiation, and wind are contradictory.

Analysis of climate change with HFAM modeling takes advantage of the detailed processes in the model. For example, temperature change can be specified by time of day and by seasons.

HFAM is able to represent:

Changes in cloudiness or solar radiation at the land surface

Changes in wind or potential evapotranspiration

Changes in rain/snow during precipitation events can all be represented

Learn more about HFAM simulations.

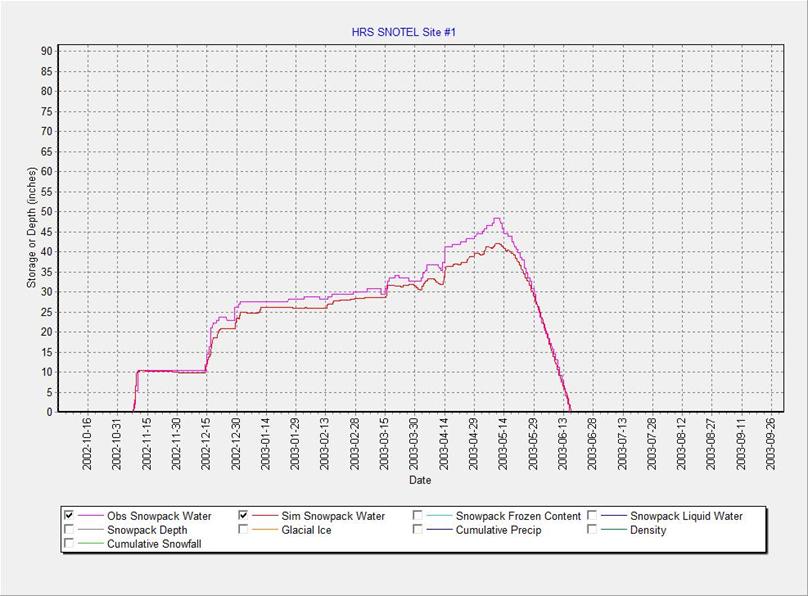

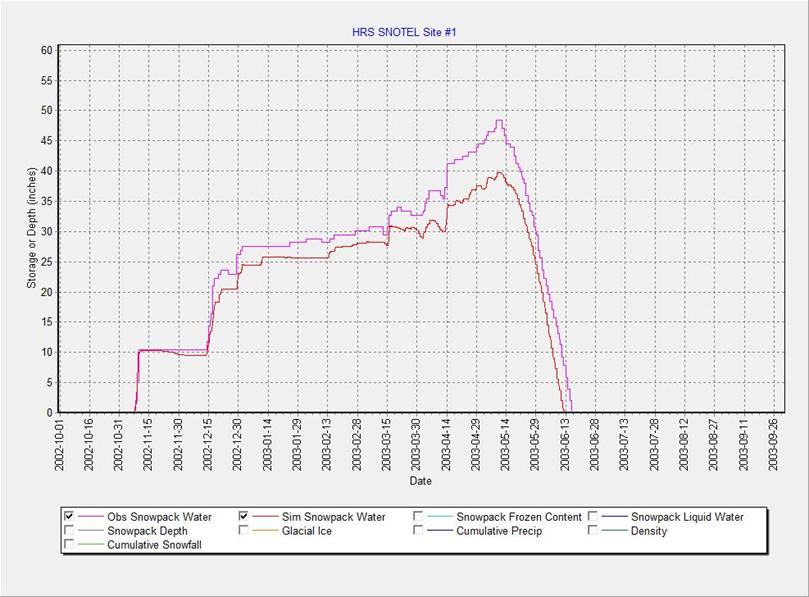

The following Figures, 2A, 2B and 2C show:

2A – Simulation of snow water content vs. observed at the HRS SNOTEL site in w. y. 2003. This site is at 8400 ft. elevation in the Upper Tuolumne watershed.

2B – Temperatures are increased + 4 deg. F. during precipitation events only. Dry weather temperatures are not changed

2C – Solar radiation (incoming) and wind velocities are each increased 10 percent. No changes are made in temperatures

The hydrological effects of climate change are watershed specific – they depend on topography, elevations, soils and vegetation – and on the physical facilities in the watershed. Denman glacier shows the sensitivity of both snow and glacial growth or depletion to small increments in temperature and precipitation (Denman Glacier).